Improved model shows gamma rays and gold at merging neutron stars

21 October 2020

The researchers, led by Philipp Mösta (University of Amsterdam), provided their model of colliding neutron stars with more variables than ever before. They considered, among other things, the theory of relativity, gas laws, magnetic fields, nuclear physics and the effects of neutrinos. The researchers ran their simulations on the Blue Waters supercomputer at the University of Illinois in Urbana-Champaign (United States) and on the Frontera supercomputer at the University of Texas, Austin (United States).

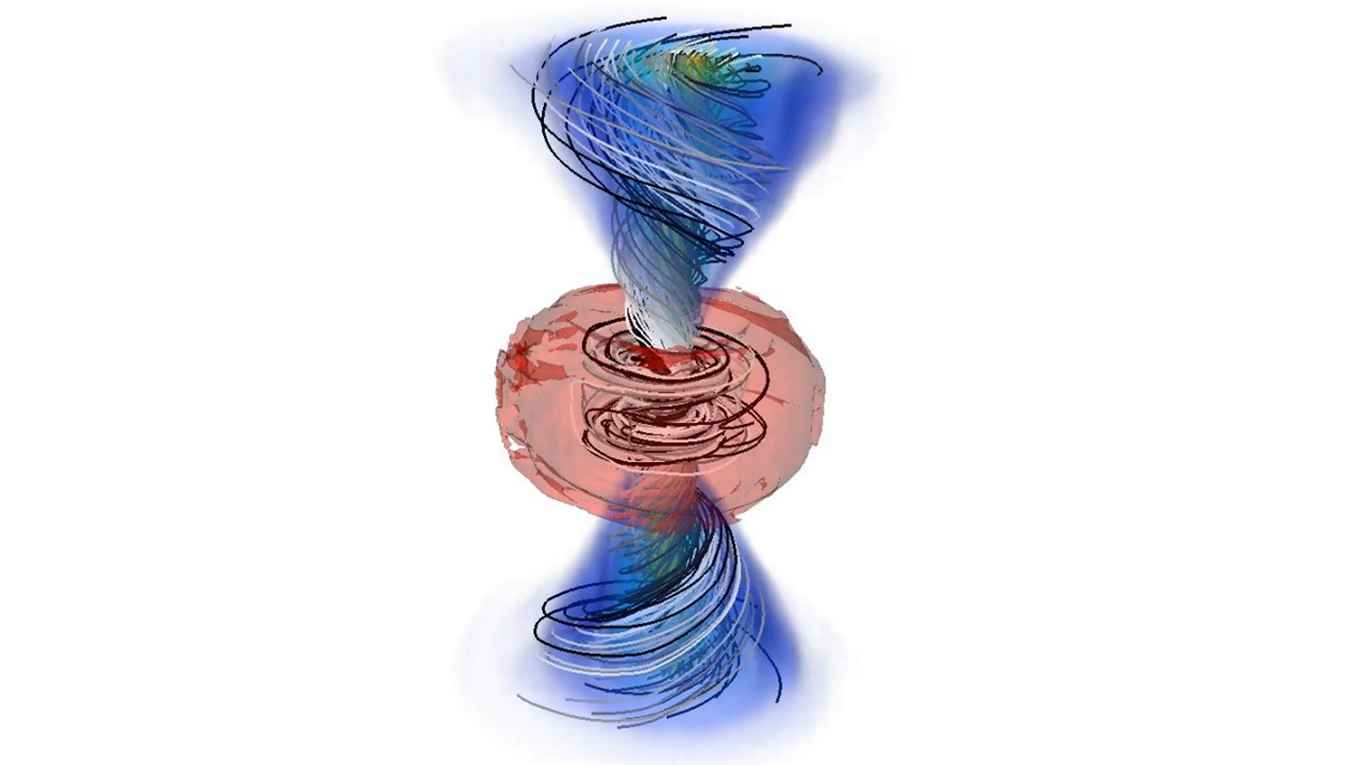

In the simulation, a ring is created around the merged neutron stars from which a thin strand of gamma radiation shoots up and down. This radiation then finds its way out like a whirlwind along the magnetic field lines of the merged stars. Furthermore, an hourglass-like cone moves up and down from the ring. This is where heavier elements such as gold possibly form. Gold is, like gamma rays, observed in the merging neutron stars in 2017 where a kilonova was formed.

Philipp Mösta: 'The gamma radiation is really new for these kind of simulations. That radiation had not appeared in the old simulations. The production of heavy elements, such as gold, had already been simulated. However, our simulation shows that these heavy elements move much faster than previously predicted. Our simulation is therefore more in line with what astronomers observed in the merging neutron stars in 2017'.

The simulations are not only meant to explain the observed phenomena around merging neutron stars. They also serve to predict new phenomena. For example, the researchers want to further refine and expand their model so that it can also deal with large stars that explode as supernova at the end of their lives and with a collision of a neutron star with a black hole