Blog: The Geminids

By PhD candidate Kenzie Nimmo

30 November 2020

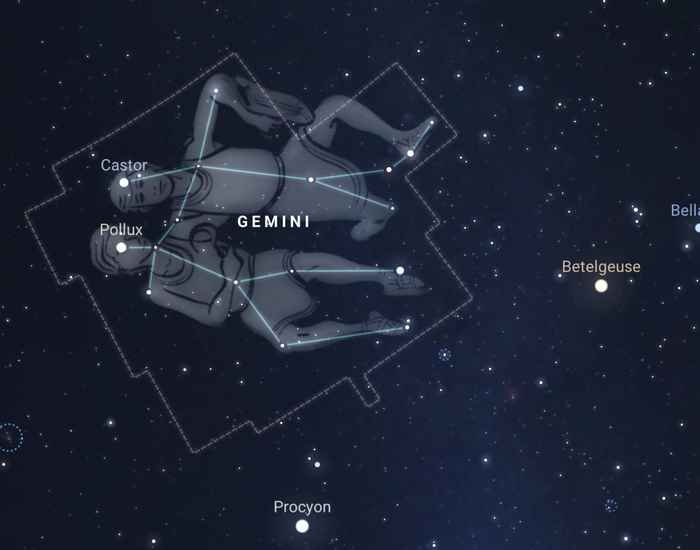

No matter where you are in the world, the Geminids are visible (given that you have clear skies and minimal light pollution). The meteors originate from the constellation Gemini (Figure 2), which is where the shower gets its name, however, the meteors can appear anywhere in the night sky.

What are meteors?

A meteor, also called a shooting star, is a piece of space debris that enters the Earth’s atmosphere, lighting up the atmospheric atoms around it. This causes most of the meteor to melt and if it’s big enough, part of it can survive and land on the surface of the Earth: this is what we call a meteorite.

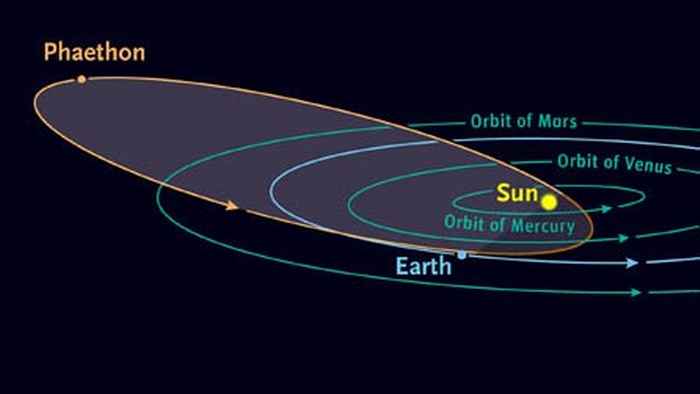

A meteor shower is a result of debris in the form of dust streaming behind a comet. The Geminids is actually a rare exception to this definition. It is produced by the stream of debris trailing the asteroid 3200 Phaethon as it approaches the Sun. The orbits of the Earth and 3200 Phaethon are shown in Figure 3 which highlights why we can see the Geminids annually.

Not only is the Geminid meteor shower a great event for amateur astronomers but it has introduced many puzzles for scientists: typically asteroids do not produce a tail of debris, so how can 3200 Phaethon produce a tail? Is 3200 Phaethon actually a hybrid rocky comet? And how did 3200 Phaethon form and end up orbiting our Sun?

I hope you get wrapped up warm and head out this December to spot some meteors in this wonderful event, and join us on December 13th for our livestream Geminids event at the API.