Blog: Parade of the planets?

13 February 2025

Here and there, unfortunately, people do exaggerate a bit how incredibly unique and/or spectacular this is, hence this blog post. For example, we are currently writing February 2025. In May 2024, we made an instagram reel, for the previous unique spectacular planet parade:

Unique?

But then, isn't this a very special time now, with so many planetary parades? Well, no. Let us explain:

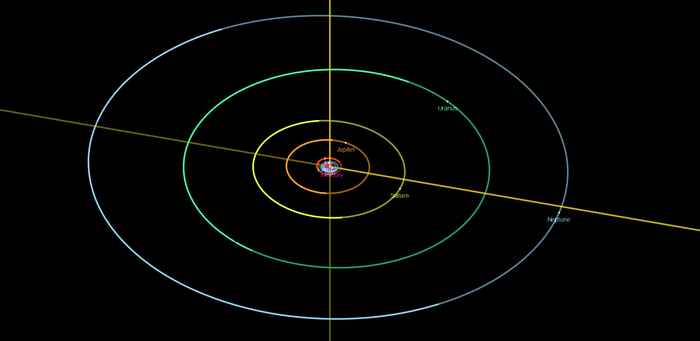

The planets all orbit the sun, some a little faster than others, with some orbiting between ours and the sun (Mercury, Venus) and some on the outside: Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune. Because the solar system was formed from a disk of dust and gas, all the planets (and the sun and moon) follow more or less the same path in the sky: The ecliptic. So it doesn't take a whole lot to make them “all align”.

Here are two schematic views from the NASA website. Click on the images to enlarge.

And what does that mean for our night sky?

The image below, created in the (free!) program stellarium, shows the night sky on Feb. 12. The red lines are the paths of the planets, the orange line is the ecliptic. The observant viewer will notice that Neptune is not included. That's right, because the planet is so faint that Stellarium's user interface didn't think it was worth highlighting it.

Then we also played a bit with the settings to show it as clearly as possible, by “turning off” the atmosphere. If we turn on the atmosphere (and with that, sunlight), you get a very different picture:

So that means that these slightly less bright planets are already not visible because of the glow of the setting sun. In the case of Saturn, this is temporary: During its opposition (the time when it was best visible because that's when it faces the sun as seen from Earth) Saturn was a lot brighter.

So how unique is this? Well, a year from now we will have another planetary parade, only Saturn will not be participating:

And MUST you look at <specific date> ? Again, probably not. It is true, for example, that on February 24 Saturn and Mercury are very close together, but this will probably be difficult to see in the glow of the setting sun.

And can you see all the planets in 1 view? Not that either, the moment you are looking at Venus, Mars is behind you.

So what's all the fuss about? It's not interesting at all?

Well no, not that either! This is and remains a wonderful time to learn where the planets are, that you can just see them with your own eyes, and how to distinguish between a planet and a star. In short: Planets twinkle a lot less than stars! And you can use apps like beforementioned Stellarium but also, for example, Starwalk or Skysafari to get an indication of where to look.

In addition, for us astronomers and astrophotographers, it is a great opportunity to take pictures and do research, and to let the people of Amsterdam enjoy this as well. Therefore, in the coming period, we will take our telescopes into the city when it is clear, to let passers-by enjoy the beauty of the universe. To stay up-to-date on when this happens, you can follow us on Bluesky, TikTok and Instagram.